A mostly technical reflection on Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants

“Meteors are not needed less than mountains”

— Robinson Jeffers, “Shine, Perishing Republic”

I recently kicked off a new outside project to build on my experience building GetCalFresh, a digital welfare assister that’s helped millions of Californian’s successfully apply for billions of dollars of food assistance from CalFresh/SNAP. While going through my contemporaneous notes from that time, I realized I had never written about another project I was deeply involved with: Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants (DRAI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Code for America published a little bit about DRAI in “Dismantling the Invisible Wall”:

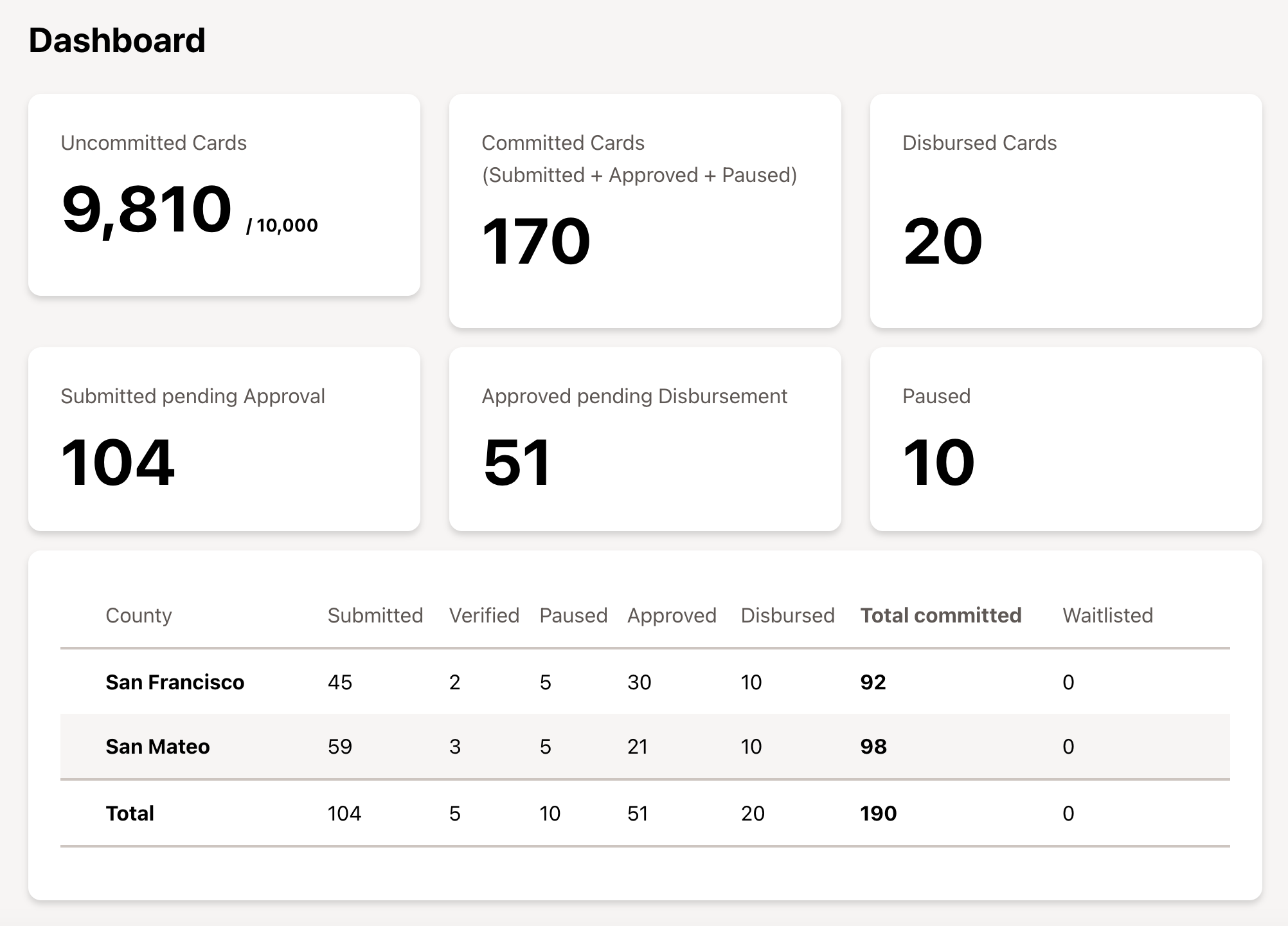

DRAI was a modest but crucial lifeline for undocumented Californians. The program’s goal was to distribute $500 bank cards to 150,000 undocumented adults who had experienced some adverse impact from the pandemic—from those who lost wages or jobs and had kids home from school needing care, to those who had gotten the coronavirus or had to take care of a family member who did. The California Department of Social Services (CDSS) selected twelve community-based organizations (CBOs) that usually provide legal assistance to undocumented communities to distribute these funds. … Ultimately, the project succeeded in distributing every single bank card to community members, putting a total of $75 million dollars directly into peoples’ pockets.

I wanted to write about my experiences with the technical bits, as I was the lead engineer at Code for America building that technical system to facilitate distribution of these vital funds during a global pandemic. This included building:

- The digital intake form, which was used by frontline assisters to read a script and collect information

- A review flow for supervisors to approve applications, screening out incomplete and duplicated applications

- A disbursement flow to issue and activate payment cards and discourage theft of funds

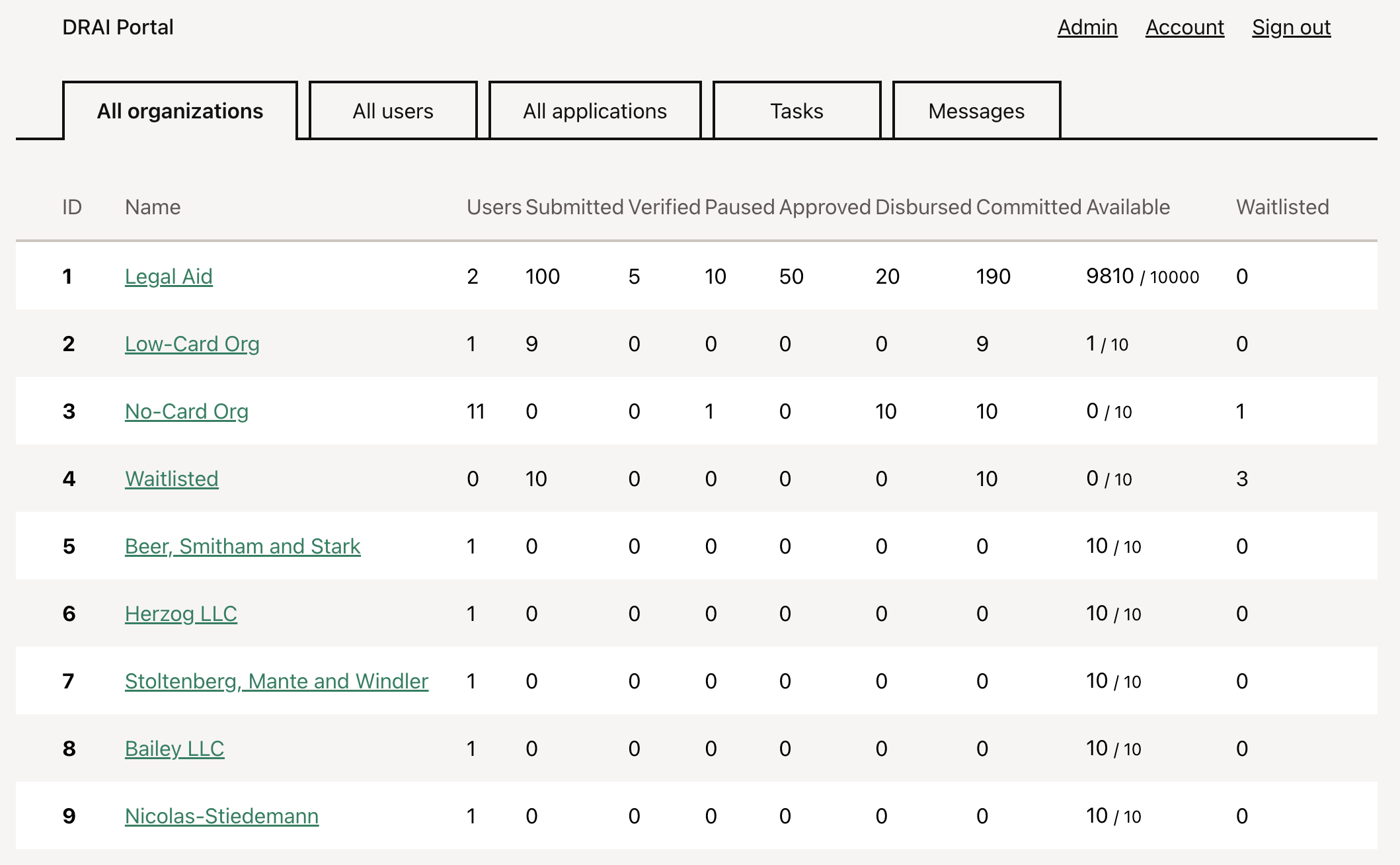

- Table stakes operational faff, like user accounts and supervisory dashboards, and audit logs and all the wayfinding and chrome and umwelt and pastiche for people to navigate from place to place in the system with as little intentional training as possible.

I no longer work at Code for America, but the code is on GitHub and I figured it would be fun to fill in some of the technical story. My screenshots contain faked seed data.

Some of the human bits

My pandemic timeline starts on March 13, 2020. That is the date San Francisco went into lockdown, as well as the date purchase offers were due on the home where I now currently live as a first-time homebuyer. That week was also fairly tumultuous at Code for America because it was in the last days leading up to CfA’s first-ever Summit conference to be held in Washington DC, and it looked like a contentious debate from my desk’s view outside the glass-walled conference rooms.

I was an engineer and manager on GetCalFresh then, and those first months of the pandemic were hard. Application intake quadrupled from ~2,000 a day to over 8,000 per day. Because the end-to-end process can take up to 45 days (even longer as government offices were overwhelmed), we were supporting an active caseload of more than 300,000 applicants every day. Code for America was then a strict pair-programming shop modeled on Pivotal Labs, and we were figuring out how best to move that culture to a remote one. And I remember, darkly, that all of us with people-management responsibilities each put together a “Continuity Plan” to document responsibilities and fallbacks should anything happen to ourselves or our reports.

My notes for DRAI from the period are somewhat sketchy about exact dates:

- Late March CfA was in talks to build the DRAI portal

- April 14 the first commit was laid down by myself and another GCF engineer

- May 18 applicants could start applying through community partners

- End of June all funds were committed

- End of July all funds were distributed

- August final reporting

- September began tearing it down

The initial team was pulled from GetCalFresh. A program manager, a product manager, a designer, a client researcher, and two engineers, one of them me. We were a high-trust group having already been closely working on GetCalFresh.

There was some initial strain in responsibilities. On the very mature project GetCalFresh, we had highly structured responsibilities: the PM and researcher decide what to build, the designer makes it usable, the program manager checks correctness, and the engineers make it work. On GetCalFresh I had to learn to work that way: “Respect for colleagues is trust in their expertise”. I’d come from labs and fellowships and early-stage startups where as a developer you just did and questioned… well, everything. So that was an adjustment back to like “um, I don’t see anyone doing this. is it, ok for me to? I didn’t hear back so I’m doing the thing.” Given the short timeline and the evolving requirements, it was largely the designer working on the intake form (which was a beast!), and myself…. designing everything else, at least in the initial weeks: entities, roles, stages, states, and how users of the system would navigate through them. A state named “disbursement” is exactly the sort of thing that’s my fault.

Of the requirements, I remember they were… vague, which is a function of the timeline, and also par for the course. I remember disambiguating “manager” from “supervisor”, asking what exactly constituted a duplicate identity and hard and soft matching and transparency (having GetCalFresh data was an invaluable resource here), and whether anyone cared to look at the specifics about how we implemented auth and 2FA and audit logging though they were (waves hands) required. Like most government-led projects during my CfA tenure, a lot more effort in the requirements was spent on ineligibility criteria than on how eligible people are expected to access the benefit or escalate when they run into trouble. And there were many calls with the frontline community organizations to understand what they needed to support and supervise their workers and administer the program. And this was during lockdown, remember.

All work is human work. My second engineer’s father, a doctor, passed away, so she stepped back and two more GetCalFresh engineers joined us. We also had a lot of help from other folks at CfA like data science and Client Success. Our CTO was totally ok whenever I asked for tens of thousands of dollars of expenditure, and our Director of Engineering had previously at no small effort streamlined our secure infrastructure with Aptible. And folks outside of CfA; a former CfA fellow and engineer at Twilio was able to get us a Short Code in under a week. Code for America has a sometimes unbearable abundance of financial and human capital, and I’m grateful and proud we were able to access it.

I wasn’t sleeping very well at the time, and had a lot of manic energy. I’d be writing Google Docs at 4am. I had started working on GoodJob just the month before. My wife and I were in the midst of IVF treatment cycles. My mom would get her first cancer diagnosis. We closed on our first home; the movers wore tyvek suits and masks. It was the middle of the pandemic. It was a time!

Of vocation, I can’t imagine working on anything better, either!

Pronunciation guide: We initially named it DAFI (Disaster Assistance For Immigrants; daffy like the duck) but then when it shifted to DRAI, no one ever was consistent in pronouncing it dry or dray. 🦆🌵🚚🤷

Onto the technical bits

Boring-ass Rails I shouldn’t be shocked by now, with so many proof points over my career, but I am: how simple it is, with experience, to respond to rapidly shifting requirements in fairly-vanilla Rails: CRUD, fat controllers, fat models, fat jobs, validation contexts, ERB, form builders, UJS, system tests, seeds, factories…. it’s not particularly difficult or mentally stimulating; it’s simply hands-on-keyboard time with the satisfaction of being done with that feature or capability and on to the next one, and the next one, and the next one. (aside: there’s a “Patterns vs Platform” thought floating around here)

A walking skeleton. It’s ingrained in me that you rails new and then immediately set up CI and a production deployment pipeline… but when I did it in pair with my second engineer for the first time, they were like “I wouldn’t have thought of doing that.” So I mention it.

An expert system. Code for America did not do expert systems, and the contemporary design system, Honeycrisp, was woefully inadequate as it was intended for big, fresh, juicy, low-cognition wizards and not tight, dry, high-density, familiarized workflows and reporting. I got to design all that! Which in practice meant running out the same thing I did at Pantheon where I also managed the usability testing program (startups!) so I felt confident in what we laid down: 🎶 Tabs and dropdowns, tables and lists; horizontal, vertical, click, click, click! 🎶

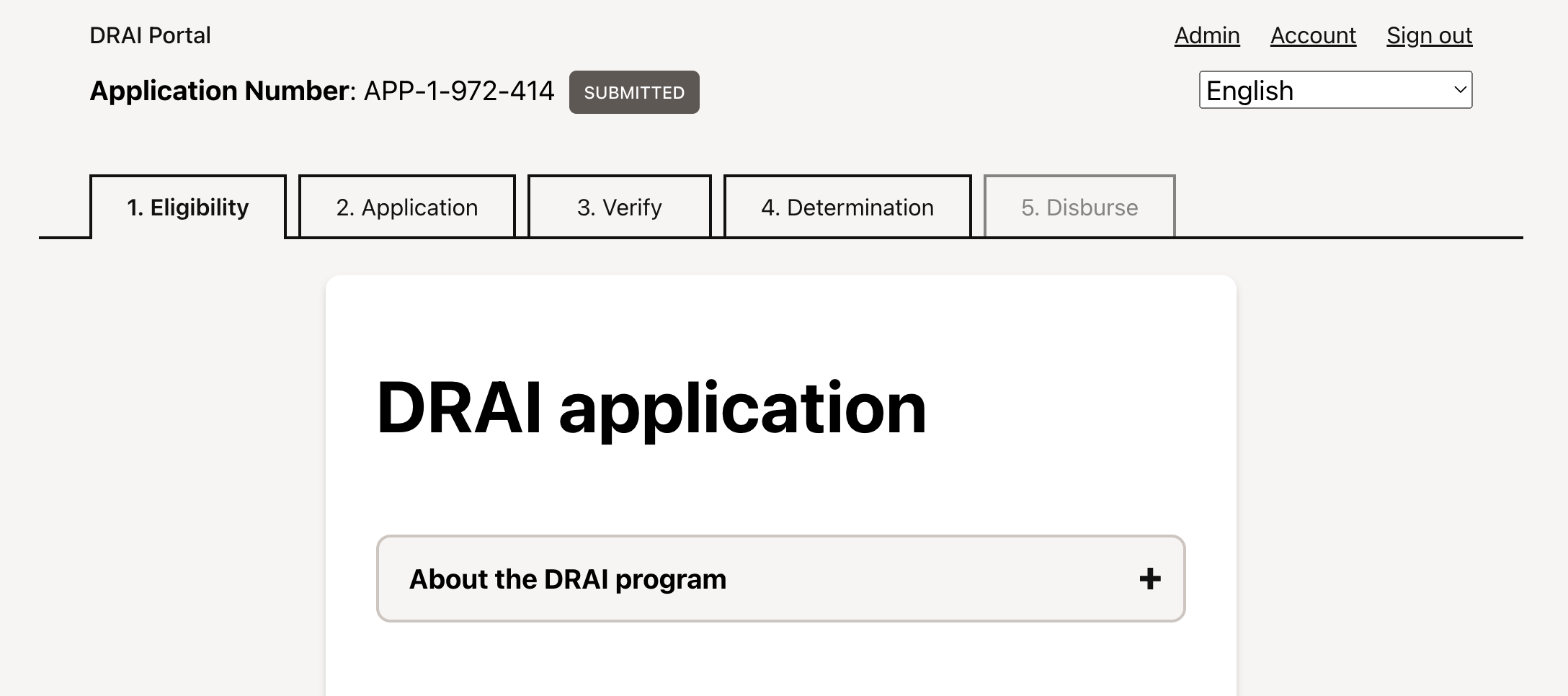

Building the plane while flying it. The most joyous, stressful part of the whole thing was that we launched the Portal with only the intake section, and then each week we frantically fixed the bugs and built the next step in the workflow process. The tabs are numbered in the order we built them, and we just had them disabled in the UI with their contents not even designed yet. I remember surprising so many folks cause we’d get an inbound email with a bug report, I’d zing back out an email confirming it, us engineers would pair on the fix, deploy, and send another email back out to confirm within minutes. Expectations in this field are so low. I think we sent had a telephone bridge and emails on Friday with like “You can now click on Step 3 in the portal”; everyone was so wired! 😰 Also, in this metaphor, the plane itself held no enduring value, we were building it to safely land at the destination.

ApplicationTexter. There was space (not a lot!) for some experimentation from experience building GetCalFresh. I have a deeper dive to write about this, but briefly: we used Action Mailer to also format and send SMS messages via a custom Twilio-based delivery method. It made sending SMS messages look the same, in code, as sending an email. I’m really proud to have upstreamed one part of it: Action Mailer deliver callbacks.

Streaming CSV. One of the needs was to generate 10k+ row CSVs so that the administering organizations could do analysis and oversight. We were able to stream them directly from Postgres.

Typheous. One of the most unique aspects of DRAI for me was that our system was activating payment cards. A supervisor would type in the number on the physical card packaging, and then the system generated a unique activation code and sent it to the card issuer, Blackhawk (who were just the best partners 💖), who’d assign it to the card, and then we’d send a message to the client with the code. Everything worked great in the validation environment with curl, but we could never get it to work with net/http or any other Ruby HTTP library. We spent way too long poking at it, together with Blackhawk engineers. And then, because we had to move on, we just used curl via Typheous. Never figured that one out.

Localization. While there wasn’t a public, client-facing part of the system, there was a lot of localization we did to make it easier for bilingual assisters to read off the application to an applicant. This meant we had a lot of mixed language pages which I had limited experience with until then, as well as incomplete translations because we were building and pushing and translating all at the same time. I had a particularly difficult time with Arabic, which is a right-to-left language and we had to patch translate to get missing-translations working properly, and I remember difficulty getting all form-inputs to be LTR regardless of the surrounding content. We did make some awesome i18n-tasks tooling for importing and exporting translations to CSV and then into Google Sheets for translators and back again.

Multiparameters. Active Record’s worst dark magic is multiparameter attributes, which is how Active Record can decompose a single Date attribute into a 3-part datefield form and back again. It’s wild! And a huge source of 500 errors when users not-unreasonably choose invalid values (“February 31”). But I also not unreasonably believe that decomposing dates is just good UX, so there’s a patch for that.

Metabase. Metabase was one of the tools I had previously introduced to Code for America, and it was invaluable on this project. We were using paper_trail gem for auditability, which produced a very rich event stream. I got real good at COUNT FILTER, JSONB querying, and some neat Metabase features like trendlines, variables, and reusing SQL questions. I’m particularly proud of how many other people were able to build wicked-good dashboards with Metabase.

Rufus-scheduler. This was my first project using rufus-scheduler as a container-compatible replacement for cron on VMs. It worked really well, and that experience was a source of my initial reluctance to build such functionality into GoodJob. (I did eventually relent in GoodJob and am happy with that too).

Factories and Seeds. A quality-of-life thing: we spent some intentional time optimizing FactoryBot factories with associations and traits to make test setup as direct as possible. And having comprehensive seeds made it no-fuss to reset one’s development database, or set up a Heroku Review App for acceptance.

Overusing Scenic Views and SQL Counts. There were several features near the end of the project that we fit in without significantly rearranging the data structure, specifically around reporting precision and a fifo-waitlisting feature. There were several messy Scenic-powered Views that used Window Functions and other complex queries; this was the source of the only significant outage I remember: joining a relation to a database view that resulted in a table scan that kicked over the database. There was also several places where we made complex association counters as optimized database queries rather than counter caches, in the spirit of this, that were messy but ok; 50/50 would do again.

Telecom Outages. The most out of our control, there was a major telecom outage during the most critical part of the project that required a lot of recovery work to ensure SMS activation codes were delivered.

ZIP to FIPS. Ok, not truly technical but when I was writing this and refamiliarizing myself with the codebase, I was reminded of how much of the work is interpreting between geographic data systems and the overrides on overrides because different parties are using different data sets from different providers and provenances. Yeeesh! This is why you save your innovation tokens by writing boring-ass Rails… to spend it on this nonsense.

Open Source. I don’t imagine I would even be writing this if the project code wasn’t publicly available on GitHub. I’ve frequently linked to bits when folks on Reddit ask for Rails examples, and for every story here I can find a reference to: a PR, a commit, a piece of code (the ticket backlog was in Pivotal Tracker RIP). In my contemporaneous notes, I discovered I had written “Week of March 9, 2020… Org Open Source Strategy Plan… license… contributing… marketing… talent”; clearly that didn’t happen at large (someday GetCalFresh, someday?) but it probably had an effect in this small, for which I am grateful to the many people who let it happen.