Two stories about technical debt, I guess

One activity I don’t enjoy very much: griping about “technical debt”; that label just never seems descriptive enough. And the things people gripe about seem to mostly fall into:

- Deferred maintenance: we haven’t updated to the latest version of X, or it’s written in A language/framework but now everyone is much more familiar with B, or we know M raises an exception at N when they O while P

- Just not the quality we expect, because reasons. It’s ok, we’re all winging it.

…and those categories crowds out the real sweaty palms stuff, the “we did do a good job but we know more now” that I think is the real deal. I can talk about that.

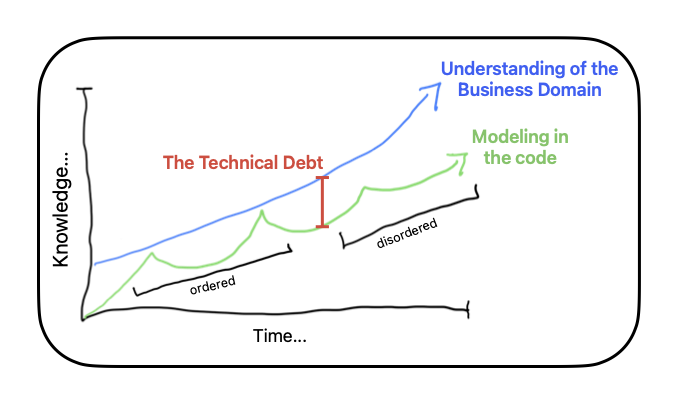

I’ve never found the particular post/video/talk? again (I’ve looked!), but it described technical debt as like: the distance between the current understanding of the business domain and the technical implementation’s modeling of the business domain. It had a chart that has stuck in my mind; it looked something like this:

That definition of “technical debt” clicked for me. For myself and the high performing teams I’ve worked with, we’re most productive, pushing value, when we’re asking ourselves: does this make sense? Given what we know now, and what we know about where we’re going, do the objects and their interactions conceptually map to how the business is being talked about by the non-technical people? Are we adapting at the same rate we’re learning? If yes, we’re golden; if sorta with some tweaks that’s good; when no… that’s bad, disordered, schismatic: carrying a burden of always translating between the language and models in the technical system and the language and concepts in the business domain. That sucks!

Aside: There’s a funny/terrifying/random thing this makes me think of: “We’ll Never Make That Kind of Movie Again”: An oral history of The Emperor’s New Groove, a raucous Disney animated film that almost never happened. One of the screenwriters describes the process of making an animated film:

In a normal four-year process, you’ve got meetings, you’ve got development people going, “What if the girl was a boy? What if the bird was a flower?” And then you have to run all those ideas.

The software projects I’ve worked on are a conveyor belt of “What if the bird was a flower?” decision making and idea running. Extend that object, repurpose this method, bolt on that, change this, swap that, rename this, better leave a comment on that. When it’s going well, it doesn’t matter that it was a bird yesterday and a flower today… as long as it’s not retaining so much birdliness that it compromises its flowerability. It’s when you’re having to remember and callback “hey, well, um, it was once a bird, fyi, that’s why it’s so much trouble to do this flower stuff”, then you’re sunk.

It’s a bad sign when forward development requires telling stories about the past.

Here’s two stories…

The isolated component

When I was working at a website hosting startup, we had one component that I could just never get the support to integrate into the larger application. It was the form that would create a new website project for the user. When the startup began, the original technical architecture was a bunch of interlinked but separated components: User Registration, User Account Management, Website Creation, Website Management, Organization Management, Agency/Reseller Management, etc. It made sense early as the business was figuring out what worked as a business, and then during my tenure we brought those components together into a unified application. Well, almost all of them.

There was a lot of give and take in the product integration; sometimes me and the other engineers would just do it and other times we’d defer it until there was a particular feature that necessitated it, and then we’d include that extra work in our estimates. It frequently took a couple passes of code cleanup and bringing it onto the design system, and that was ok. That’s the job!

That last, last, last component of Website Creation eluded us though, and it was outside our control. At that point, development was transitioning from “engineering led” to “product management and design led” and I had been instructed that engineering couldn’t make any product changes unless they were connected to an active PRD (Product Requirements Document) controlled by the PMs.

There was plenty of demand to make changes to Website Creation: smooth out the first-time account registration flow into creating a website; allow the user to do some activities in parallel while the website was spinning up like inviting team members or perusing billing levels; decouple the concept of “a website is a marketing strategy” from “upload your code and have some containers and a load balancer provisioned” so that non-developers could still plan a website without invoking all the technical bits.

But not enough appetite to get it done.

Of “technical debt”: everyone except our little engineering team maintaining the frontend didn’t think anything special of Website Creation. It wasn’t obvious unless you carefully watched for the hard-browser refresh, or noticed the navigation bar change slightly. Conceptually it was a unified product (heck, I even remember a product launch called “One”), but the work hadn’t yet been done on the application side and we engineers carried the burden.

It was funny because every time a product change that touched Website creation was discussed, the same thing happened:

PM: Your effort estimate seems really high. What’s going on?

Me: Well, this involves Website Creation and it’s still its own component and can’t access any of those other systems that are necessary to build the feature. We’d need to bring it into the rest of the application. It’s definitely possible! There’s a few open questions with product and design implications, so we’d need to work together on that.

PM: Oh, well, huh, I didn’t expect that. Hmm, we don’t have the bandwidth for all that. Let’s pass on it for now.

This happened multiple times! It was weird too because the particular project being planned would be spiked, and then the engineering team would have to wait around while a new project was spun up and that likely took just as long as it would have taken to do the work on the Website Creation component. If I hadn’t been explicitly told to sit on my hands otherwise, I would have probably just done this as off-the-books, shucks-I-didn’t-think-it-would-be-a-big-deal, shadow-work.

It never got done during my tenure; I think they later decided the problem was that the whole thing wasn’t written in React 🤷

The campaign message

When I was a developer on GetCalFresh, the functionality with perpetually unexpected estimations was “Campaign Messages”.

GetCalFresh would help people apply for their initial food stamp application, at which point it would be sent to the applicant’s county for processing. Over the next 14 to 28 days the county would schedule an in-person or telephone interview, and request various documents like pay stubs and rental leases, and the applicant would have to navigate all of that. (The administrative state suuuuucks!) To help, GetCalFresh would send a sequence of email and/or SMS messages to the applicant over this time period explaining what was needed and what to expect next. A messaging campaign, y’know, of “campaign messages”

When GetCalFresh was first laid down in code, there were two “types” of campaign messages: General and Expedited. Under a couple of different circumstances, if an applicant is homeless or at risk of being homeless, or has no cash-on-hand to purchase food, their application is eligible for expedited processing and thus we’d send them a message sequence over ~14 days; everyone else would receive a message sequence over ~28 days. We were sending the same messages, just on a different schedule.

So when we engineers were then asked to customize a message, like “if the applicant is a student, add this description about their special eligibility”… we just if/elsed it on in there. Oh, now this county is piloting a special process, let’s make a little carve out for them too and swap this message. Still, same sequence, just tweaks, right? Well, all those small tweaks and carve-outs build up, and all of a sudden we’re having to ask “ok, so you want us to rewrite this one itty bitty message, well we also need you to specify what it should be for students, who do and don’t qualify for County X’s special process too”. It got twistier and twistier. And when requests like “don’t send that message in this special circumstance” or “add a totally new message but just as this one-off” came in, we’d be like “totally possible! and that’s gonna take more work than you think!”

GetCalFresh had the best Product Managers I have ever worked with in my life, and we still got locked into a similar loop as the last story: we’d do our estimation with the PMs, it exposed the fruit hung more high than low, and the change would be deprioritized. I think the PMs got it, but the challenge was that the other folks, client support and the folks coordinating with the counties and the datascience team, would be like “we heard that Engineering doesn’t want to build it.” So weird! Not engineering’s call! (Aside: I spent so much time coaching non-technical stakeholders on how to work in a PM-led system, but always more coaching to do.)

I remember making a Google Doc to analyze why and explain how the system we initially designed for (same sequence of messages with different schedules) didn’t match our understanding of the problem today. The doc listed out all of the different reasons we knew of why we might customize the message. It was at least 10 bullet points. And there were a lot of other learnings too: initially we designed around customizing for just 3 major county systems (State Automated Welfare Systems - SAWS), but later found ourselves doing county-by-county customizations (California has 58 counties). I advocated for configuring each county in its own object despite the scale brainworms demanding a singular and infinitely abstracted model (I call these things “spreadsheet problems” when you can simply list the entire domain in a spreadsheet).

Of “technical debt”, I still can replay in my brain the deliberate mental spatial shift of imagining the campaign model as a 2-column array (General and Expedited) with 10+ rows of logic shifts and then flopping it onto its side to make a change. All that mental context has a huge carrying cost that all of us had to budget for when making a change.

During my tenure, we never did the significant reworking to how campaign messages were implemented, though some bold colleagues did their best to make changes as safe and simple as possible with DSLs and test macros. Thank you! 🙏

That’s it

Sorry, no great lessons here. Just stories to share (“ideally you’d try to see it as a funny story you can tell friends rather than a hurtful snub that needs to bother you”) I mentioned coaching folks on working with PMs, and I think the frequent advice I gave non-technical folks probably holds true for engineers too when asking:

Always have your top 3 ranked work items ready to go when talking to decision makers (the PM?). Don’t bring new stuff unless it changes those top 3.

(I mean sure, share context and adapt, but allow yourself no doubt that you’ve’ clearly and consistently communicated what your top priorities are before they get dumped in with everyone else’s.)

(But also, if you’re an engineer and you can and no one is breathing down your neck, simply get it done and celebrate. The PM doesn’t have to lead everything. You can do it! 👍)