Environment, at work

Gaia

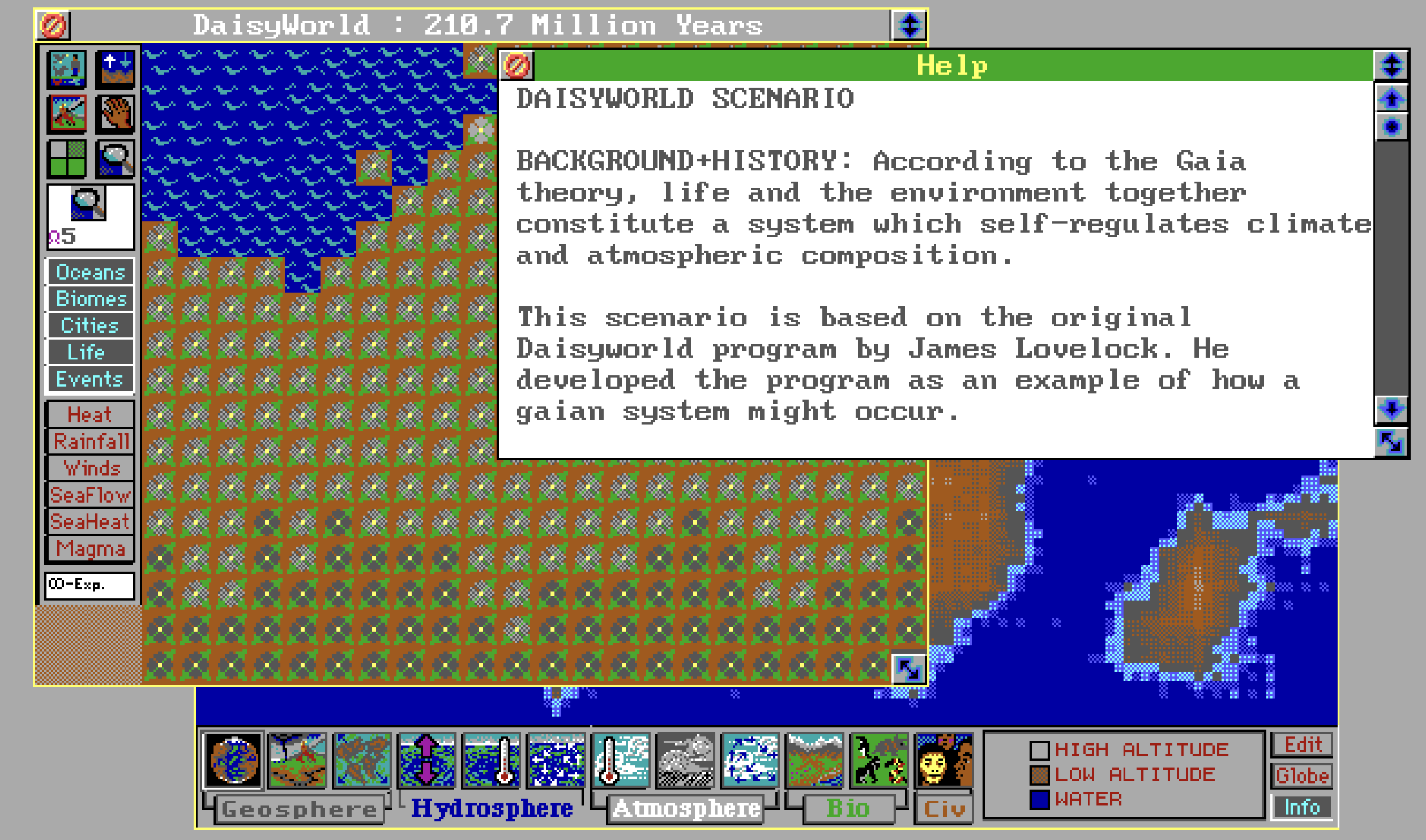

I played a lot of Sim Earth as a kid. It had a mode called Daisyworld based on the “Gaia Hypothesis”:

proposes that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a synergistic and self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet.

In Sim Earth’s Daisyworld, that was simulated by populating the Earth with different shades of flower. Darker flowers survived at lower temperatures and absorbed sunlight, warming their immediate environment; lighter flowers survived at warmer temperatures and reflecting sunlight, cooling their immediate environment. Running the simulation would, eventually, usually, lead to a dynamically changing, but still steady-state environment; in Conway terminoloy: still lifes and oscillators.

Usually your Earth found a steady state, unless:

- geographical barriers prevented regulating changes from spreading, like mountain ranges or island archipelagos; or

- disasters like volcanoes or meteors significantly disrupted the environment before the flowers could adapt and moderate it; or

- you plopped some bunnies or herbivores that ate the flowers, because the Gaia mode didn’t lock-out the other Sim Earth tools. Sandboxes!

Usually your Earth found and could recover a steady state! That’s homeostasis:

Homeostasis is brought about by a natural resistance to change when already in the optimal conditions, and equilibrium is maintained by many regulatory mechanisms: it is thought to be the central motivation for all organic action.

Terroir

From Vicki Boykis’s “The Art of the Long Goodbye” :

A few years ago, I read the Southern Reach trilogy, by Jeff Van Der Meer….

One of the main concepts of the books is the idea of a terroir, a self-contained natural environment that shapes everything inside of it. Usually when we talk about a terroir we’re referring to wine: a wine from a given region tastes like wine from that given region should taste because of the grapes and the soil and the way the sunlight hits that particular spot. Since I left my last job, I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of terroir as it relates to the workplace.

Every workplace, like every Tolstoyan family, is unique in its own way. When we start a job, we enter that terroir with the intent to shape it. But in turn, we are also shaped by it.

Landrace

A landrace is:

a domesticated, locally adapted, traditional variety of a species of animal or plant that has developed over time, through adaptation to its natural and cultural environment of agriculture and pastoralism, and due to isolation from other populations of the species.

As I’m now in the land of big companies, it’s very common to hear someone described as “from Amazon” or “from Microsoft” and like, I know what they mean!

One of my challenges as an engineering leader during the pandemic was this: how much do we adapt our values and practices to be inclusive to the current fucked-all-over situation while preserving what made us, as an engineering organization, us. I think my results were mixed.

An example: pair programming. We were a lot of people from Pivotal labs (there it is!) with a strong belief in Extreme Programming: shared ownership, an active-closeness to the users of our software, and closeness to each other through frequent pair programming. And we went from largely in-person pairing, to remote pairing. I find pair programming to be exhausting in the best of circumstances, and the ongoing pandemic didn’t help. So we adapted our values and practices, and de-emphasized pairing and went from an expectation of “most of the time” to “a tool that’s available some of the time”. It was a stretch (aside: it wasn’t just pairing that got stretched either, the whole XP thing)

A team is never static. People were leaving, we were hiring, teams were forming and reforming. It was tenuous for everyone, to test out the limits of inclusion and identity. And as an engineering leader, it led to a lot of tough conversations about how… we… work… together. It was hard; I think we lost that cultivar.

Oasis

Will Larson writes about this idea of a “Values Oasis”:

A few years ago, I heard an apocryphal story about Sheryl Sandberg’s departure from Google to Facebook. In the story she apologizes to her team at Google because she’d sheltered them too much from Google’s politics and hadn’t prepared them to succeed once she stopped running interference. The story ends with her entire team struggling and eventually leaving after her departure. I don’t know if the story is true, but it’s an excellent summary of the Values Oasis trap, where a leader uses their personal capital to create a non-conforming environment within an wider organization.

Garden

The relationship between people and environment is a problematic metaphor.

I was a member of the Boston Pubic Garden’s Rose Brigade for number of years, taking care of the roses. The Boston Public Garden’s style is Western, specimen, ornamental: large, well-spaced bushes with well-defined blooms. They’re gorgeous. And.

There’s a lot of waste. Trimming, dead-heading, opening up, clearing leaf drops. A lot of waste.

There is a trope, Cincinnatus, in which the tyrant/general/magnate retires (or desires to retire, after the present crisis, of course) to tend garden. I think it usually appears to soften them: see they can be gentle too. But I dunno, gardens aren’t gentle. There’s a lot of centering the gardener, and a lot of will to be exercised in a garden. Other people aren’t plants, don’t take it too far.

I’m reminded of Nirgal’s (spoiler!) fated ecopoetic basin in KSR’s Blue Mars:

Nirgal wandered the basin after storms, looking to see what had blown in. Usually it was only a load of icy dust, but once he found an unplanted clutch of pale blue Jacob’s ladders, tucked between the splits in a breadloaf rock. Check the botanicals to see how it might interact with what was already there. Ten percent of introduced species survived, then ten percent of those became pests; that was invasion biology’s ten-ten rule, Yoshi said, almost the first rule of the discipline. “Ten meaning five to twenty of course.”

And close on it out with a quote from Seeing like a State:

Contemporary development schemes… require the creation of state spaces where the government can reconfigure the society and economy of those who are to be “developed.” The transformation of peripheral nonstate spaces into state spaces by the modern, developmentalist nation-state is ubiquitous and, for the inhabitants of such spaces, frequently traumatic.