Put Your Civics Where Your Houseplant Is

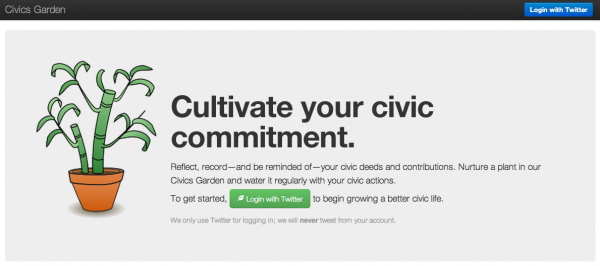

The core assumption of engagement applications is that people will do an activity consistently and repeatedly if you just structure the experience and incentivize it correctly — even if it’s asinine. The justification for civic engagement apps can be similarly foolish: people will perform a potentially beneficial activity that they aren’t currently doing if we give them the ability to do it on the internet (or via SMS, or iPhone, etc.). That’s why I built Civics Garden.

A few months ago a Code for America email thread came around asking how “If you could tell the story of how government works, what would you say?” I pushed back with the idea that one cannot know government without participating in it, and since we are a government of, by, and for the people, the best place to start would be reflecting on one’s own civic life and civic actions.

A tried and true method of reflection is journaling. Hundreds of millions of people keep a journal called Twitter, reflecting and writing on their days experiences, tribulations, meals, and cat sightings (this is not a comprehensive list). If people naturally do this, why not ask them to reflect specifically on their civic actions—voting, volunteering, checking out a library book, picking up a piece of trash, smiling at a stranger—and write down that reflection (however brief) on a regular basis?

Projecting from my own nature, people are fickle, lazy, unreliable creatures. That’s why gamification is the hotness. “How can I get you to look at my ads every day? I’ll make it a game.” Sure, this is no different than historical incentives (“How can I get you to work in my coal mine? I’ll pay you money.”), but now it’s on the internet where advertising is easier to place than coal mines. One form of gamification I really enjoy are virtual pets: like tomagatchi’s you feed with Unit Tests, or flowers you water with foreign language vocabulary. They encourage you to perform an activity because you instinctively (unless you’re a sociopath) feel good when they’re healthy and bad when they’re sickly… despite the fact you know they aren’t actually alive.

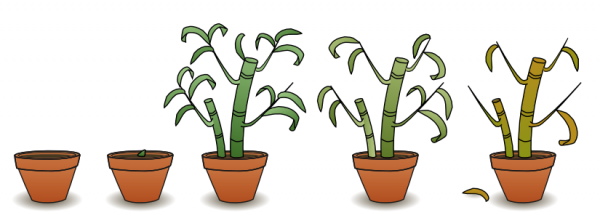

Civics Garden combines these concepts: by signing up, users adopt a virtual plant that they keep healthy by regularly “watering” it by writing down their civic deeds. If they go too long without a journal entry, the plant will wither and eventually die. Just like owning real houseplants, it has exhilarating potential.

I built Civics Garden with Node.js and MongoDB using Twitter for authentication. Each new user receives a healthy bamboo plant to caretake by writing short journal entries. To keep people reflecting regularly, one’s plant will wither after two days, and die after four–though users can replant it as many times as necessary. To keep them coming back to the site, users receive a tweet from @civicsgarden to let them know when their plant needs refreshing. As an minimum viable product (MVP), it’s high-on-concept/low-on-looks, but Diana and Emily helped with the graphics.

I’ve tested it internally with Code for America fellows and it should be a rousing success. All of us, as active civic participants performing important civic deeds should be able to briefly but consistently reflect upon and record our actions, right? See for yourself on Civics Garden and test your ability to reflect on a healthy civic commitment.

…or maybe people just don’t like bamboo.