Below is an excerpt from my final paper for the Critical and Creative Thinking course I took this Fall. I based my paper on a quote from the Arthur Costa, author of our textbook, who wrote:

Most authors and developers of major cognitive curriculum projects agree that direct instruction in thinking skills is imperative. Edward de Bono, Barry Beyer, Reuven Feuerstein, Arthur Whimbey, and Mattew Lipman would agree on at least this point: That the teaching of thinking requires that teachers instruct students directly in the processes of thinking. Even David Perkins believes that creativity can be taught—by design.

The question I investigated was if these major authors and developers agree that critical thinking can be taught, on what aspects of teaching do they disagree? To write the paper, I investigated the backgrounds of those 6 individuals and then placed their major works into an analytical framework. It actually turned out easier than I first expected because in my research I discovered a paper that had already created such a framework: Yoram Harpaz’s “ Approaches to Critical Thinking: Toward a Conceptual Mapping of the Field”. So my work was mostly to synthesize and connect around my question.

The 3 major approaches to Critical Thinking are:

The skills approach: thinking tools are used efficiently—quickly and precisely—in given circumstances. Rather than imparting knowledge to students, they should be trained in proper thinking skills. These thinking skills can include strategies, heuristics, and algorithms as well as seeking precision or efficiency when thinking.

De Bono (Physician) – CoRT

Beyer (Education/Pedagogy) – Direct teaching of thinking

Fuerstein (Cognitive Psychologist) – Instrumental Enrichment

Whimbey (Instructional Designer) – Problem Solving

Lipman – (Philosophy) Philosophy for Children

The dispositions approach: motivations for good thinking are formed by reasonable choices. The focus is not upon a student’s ability to think, but rather upon motivation or decision making to think critically about a particular situation or action.

Lipman (Philosophy) – Philosophy for Children

Perkins (Mathematics & AI) – Dispositions theory of thinking

Costa (included because his quote is the inspiration for this paper) – Habits of mind

The understanding approach: the ability to locate a concept in the context of other concepts or implement a concept within another context. “Thinking is not a pure activity but activity with knowledge; and when this knowledge is understood, thinking activity is more generative (creates better solutions, decisions and ideas). Understanding therefore, is not (only) a product of good thinking but (also) its source.” [ Harpaz]

Lipman (Philosophy) – Philosophy for Children

Perkins (Mathematics & AI) – Understanding performances

Here’s my conclusion:

Interestingly, the majority of theories and works cited fall under the skills approach. In addition, both Lipman and Perkins fall under more than one approach; Lipman falls under all three. Lipman and Perkin’s wider frame could explain this: both approach the teaching of critical thinking from a frame of philosophy rather than psychology or cognition.

Though it was not known when this paper was first conceived, this paper ascribes to the understanding approach. By placing these individuals’ theories and works within the context of critical thinking pedagogy, and relating them to each other, these theories and works can be both better understood and applied.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

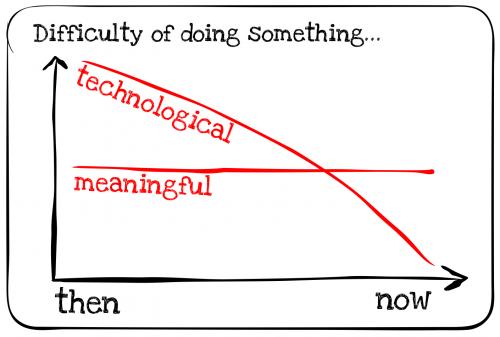

Visualizing the demand curve is left as an exercise for the reader.

Visualizing the demand curve is left as an exercise for the reader.