A subchapter on art from K.C. Cole’s Something incredibly wonderful happens: Frank Oppenheimer and the world he made up.

A Matter of Urgency

“It’s through familiarity with the arts that I think we will make the kinds of changes that make life stay human.”

A respect for aesthetics, Frank thought, should be a central part of sound decision-making. He didn’t think it would be out of place — though he admitted it would be impractical — if Congress, unable to decide on a difficult matter, took a recess to visit the National Gallery for guidance. “Art,” he liked to say, “is not valid merely to decorate our surroundings with statues in the plazas of skyscrapers, any more than science is valid because it provides the conveniences of electric shavers.”

When people said, “We need more art,” Frank complained, they tended to say it in the same tone of voice they used to say, “We need more trees.” True, both art and trees make our surroundings more pleasant, but artists also make discoveries about nature and human nature that are on the same level as the discoveries scientists make. And in the same way that we can make better decisions about global warming if we know what scientists have discovered about the earth’s changing climate, so we can make better decisions about human affairs and environments if we pay better attention to what artists have learned.

Frank worried a lot that the arts were undervalued, and that aesthetic considerations were largely ignored whether people were designing schools, supermarkets, bridges, or “topless dance joints, nuclear weapons, and homes for the aged.” If money was tight, aesthetics was the first thing to go. “We’re in terrible trouble because of that,” he said. Historically, places that respected the arts and based decisions on aesthetics were also places where “better things happen,” he argued. If art were considered more important, he wrote to David Rockefeller, “many of the things that now shock or degrade people’s sensitivities would not be tolerated.”

Of course, as a physicist Frank had learned to trust aesthetics. Scientists often try things because they “smell right.” They believe in theories because the mathematics behind them are “beautiful,” even when they contradict evidence. Like artists, scientists develop an eye (and ear) for nature, a sense of what is true and what is not. Laypeople, too, should be encouraged to rely on their aesthetic sense to guide their decisions, Frank thought; if a certain course of action or behavior struck them as “ugly,” then it probably was.

Artists and scientists, Frank liked to say, are the official “noticers” of society — those who help us pay attention to things we’ve either never learned to see or have learned to ignore. Artists of all ages and in all lands have traditionally sensitized people to nature through their poetry and painting, sculpture and drama, and, less obviously, through their music. Without art, “one even ignores what people’s faces are like,” Frank said, “but by seeing paintings of people’s faces you begin to look at them again, and I think that the same thing is true of science. You look at the sky and you see the stars, and it is just an amorphous mass; but suddenly somebody talks to you about it and you see that some stars move with respect to other stars.”

He gave artists credit for teaching us great human truths. Without art we might not have recognized the universality of the feeling between mother and child, he said, or the emotion between man and woman.

“If you don’t know how to notice, you can’t do anything well,” Frank said. “You can’t even relate to people well.” You can’t tell if someone is angry or amused or hurt, or if the weather is about to change and maybe you should get an umbrella. You’ll miss that guy lurking in the shadows, and Saturn shining overhead.

Frank wondered why urban planners didn’t look at paintings in order to learn how to design cities; why architects didn’t look at Cezannes to design cafés; why people didn’t look at portraits to find meaning and wonder in the transformations that occur in aging faces and bodies. Why didn’t people realize that paintings enable us to find pattern and structure in scenes that would otherwise seem shapeless, amorphous, and emotionless?

So above all else, the Exploratorium was a place that encouraged the kind of everyday noticing that helped people develop an eye and ear and feel for the social and physical universe aroundthem — an almost artistic sensibility.

Visitors to the Exploratorium certainly build up intuitive feelings for physical phenomena as much from artistic works as from “science” exhibits — whether the subject is wave mechanics or the nature of light or fluid dynamics or the quantum properties of matter. To this day, when I imagine stars being born from swirling interstellar clouds, I think of Ned Kahn’s “Whirlpool”; when I think of exotic bits of matter coming into being seemingly out of nothing, I see his “Visible Effects of the Invisible.” Most of my intuitive feel for light and color and shadow and reflection comes from Bob Miller, and there is a lot of the spinning black hole in Doug Hollis’s “Vortex.”

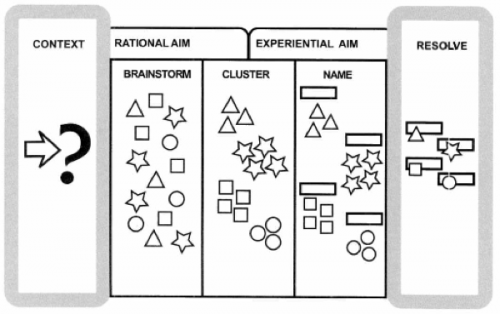

Even in terms of process, Frank pointed out, artists and scientists work in similar ways. They both start by noticing patterns in space and time, trying to make sense of them, rearranging them, and then linking patterns together in ways no one had thought to do before. They make sketches with equations or charcoal. They elaborate and synthesize. “They end up with a composition which means more than what they started with,” Frank wrote — melodies and theories. In essence, they make patterns of patterns that reveal new insights. Their compositions, theories, and other works separate relevancies from trivialities; provide a framework for memory; reassure by creating order out of confusion.

Of course, all people spend much of their time perceiving and making sense of patterns; even animals do it (the dog knows exactly what follows the fetching of the leash). Frank once told me that when he can’t see a pattern, he gets “miserable.” But artists and scientists spend their whole lives looking for patterns in nature, and so perhaps learn to see more than the rest of us.

To Frank, artists were people who looked at human experience in the same way astronomers looked at the sky through telescopes. Just as astronomers collect, codify, interpret, and communicate what is known about the stars, so artists collect, codify, interpret, and communicate what we know about human feelings.

The reason we need this knowledge so much, he argued, is the rapid pace of change. If things didn’t change, then perhaps education could simply be a matter of learning to conduct business and follow directions. But everything in nature changes. People inevitably change the world in which they live. They change themselves. And as people(s) change, at some level there’s always a worry that we might lose some of that indefinable and extraordinary specialness that makes people human. And who can define that essential nature of humanity we so want to preserve? Who can tell us (or remind us) what is fine, what is beautiful, what is important, in humankind? Frank claimed that was the role of artists.

Decisions about how to adapt to inevitable changes are based, by necessity, on what we believe is possible. Science tells us what is possible in the physical realm, and in doing so, gives us a basis for action. If we don’t know that it’s possible to make antibiotics, for example, we won’t learn how to protect ourselves against disease. In the same way, Frank thought, art tells us what is possible in human experience. What’s more, it tells us how we feel about the various possibilities or at least how an individual artist feels, and therefore one way it is possible to feel. “If you don’t know those things, you are not going to make good decisions,” he said.

And just as technological inventions help us cope with changes in the external environment, we need “heightened social and emotional awareness and invention,” Frank said, to cope with changes in the human environment.