Last year I interviewed Richard (Dick) Howe, Lowell’s Registrar of Deeds about the impact of his participation in a Community Mapping class I taught at LTC in Spring, 2006.

The interview came about as a result a NTIA administrator asking the Transmission Project for evidence of a community training initiative that resulted in the creation of something of lasting economic or social value to a community, specifically a brief “ example in which tech training –> spurs creativity –> results in innovative outcome”.

This is what I submitted:

As a result of community technology training, the city of Lowell, Massachusetts better targeted public safety resources during the foreclosure crisis. After attending classes on online community mapping offered through the local Community Media Center, Lowell’s Registrar of Deeds created a series of maps of foreclosed properties in the city. These maps helped the city government see foreclosures not as isolated incidents but as patterns within specific neighborhoods. This analysis allowed the city to better target these areas in distress with police and public services, helping reduce the safety and community impact of foreclosed and abandoned properties. Speaking about the online community mapping class, Registrar of Deeds Richard Howe said “Beyond the nuts and bolts, it was inspirational and opened my eyes to that type of technology”.

Beyond that brief summary, my interview with Dick gave me a lot of insight into how he benefited from the online community mapping class—benefits I hope I and others are able to reproduce in all their technology trainings. Those benefits Dick explained fell into three broad categories: functional skills, a greater general appreciation of technology, and a sustained curiosity for the topic.

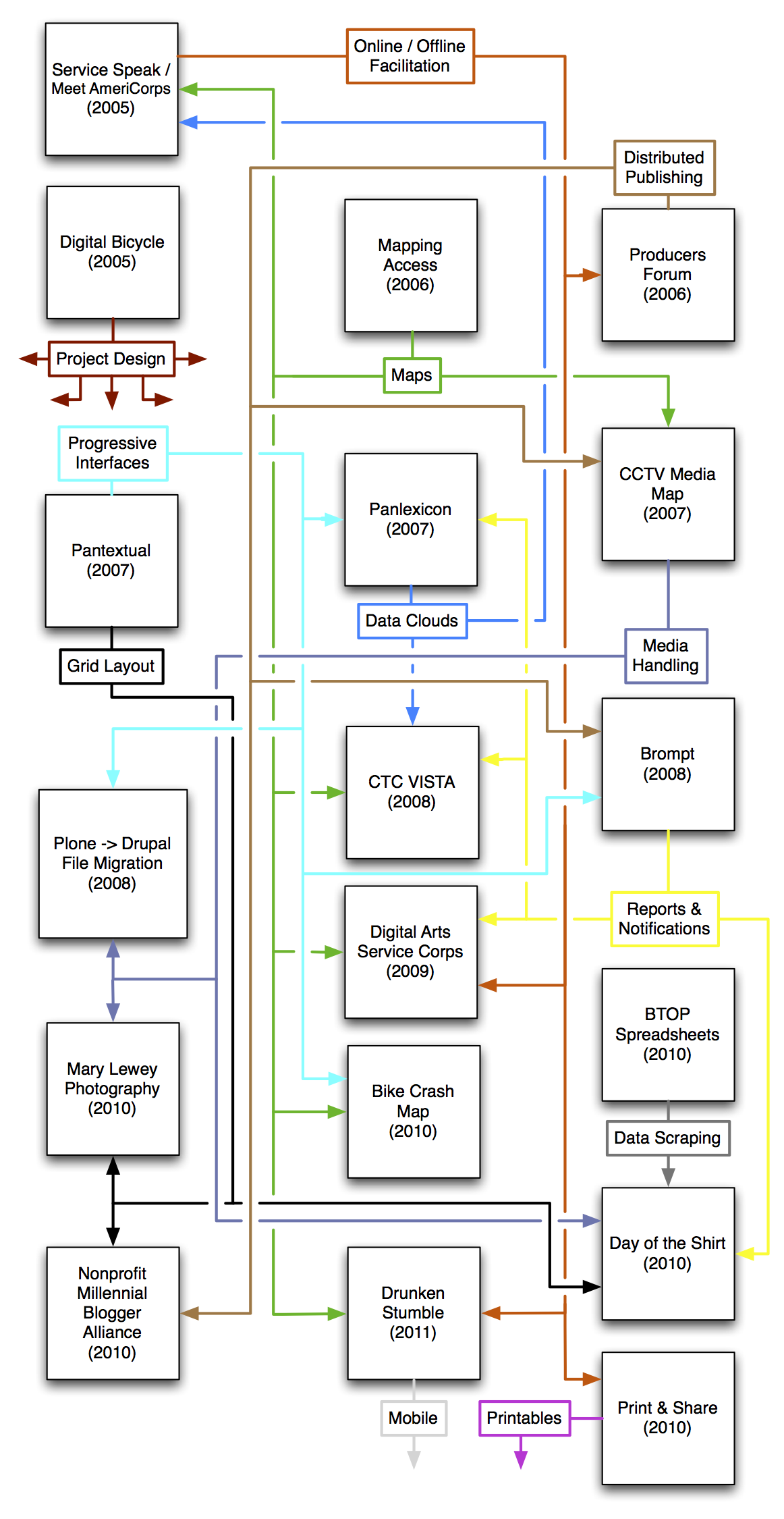

Function Skills: 1. As a result of Dick’s participation in my class, he gained the functional ability to create map mashups using tools like batch_geocode, Google Maps, MapBuilder.net, Platial, etc.

Dick used these skills to plot foreclosures in Lowell, extracting data from the registration of deeds and creating map mashups to show geographic distribution. These maps got some attention from the Lowell Sun newspaper and the Lowell City Council, alllowing them to “see” neighborhoods or sub-neighborhoods with significant foreclosures. These maps helped the city to allocate resources (police, public services) in a more rational manner and helped shift the perception of foreclosures from isolated events to more systematic patterns. That helped the city direct limited resources to issues caused by crisis (abandoned properties, crime, etc.). Without a visual depiction on a map, planners and public servants would have had to rely on their knowledge of the city.

On his personal blog, Dick mapped campaign contibutions for congressional and county seets. He took data from the campaign contributions and mapped where residents were contributing from.

An issue Dick identified though was that he never cracked through to a larger scale. He created the maps manually and because of geocoding limits, he would have to break the dataset down by neighborhood before recombining them. He further has had difficulty making the climb to more advanced tools like ArcGIS.

**Greater appreciation of technology: **For example, on his blog Dick takes pictures of olding building in Lowell. When he purchased a new digital camera, one of the big selling points was that the camera imbeds GIS data into the picture. Furthermore, Dick says he now is always on the lookout for websites and apps to use for communications:

“I was given imagination and vision on how it can be used,” he said. “If a project came along, I’d have the motivation to figure it out.”

Sustained curiousity: Dick says he is more likely to look behind the scenes of technology and do stuff. During the class I talked about the power of Drupal and its plugability and CMS features, which we were using for mapping. This led Dick to create a Wordpress blog and move off of Google’s free services. He’s now teaching himself PHP & MySQL.

“It got me interested to look under the hood” Dick says, and gave him confidence to to try things that he would otherwise have thought were too hard to use, but is more functional and tailorable to what he wants.

In his work as the Registrar of Deeds, Dick uses the knowledge and experience he gained in class. Working with different state agencies and contractors, like MassGIS and Applied Geographics, he is trying to better link deed and ownership information with maps, shapefiles and photography resources. Dick does though see difficulties in the bureaucracy as different priorities, such as access-limitation and security, results in pushback. He takes the long view: it’s a failure of imagination today but folks will catch up eventually.

Ultimately, Dick said the class “Raised my sights and capabilities to the stuff that can be done.”