The Tree of Knowledge is a goldmine of concepts and ideas. The most interesting parts are at the end—in discussions of society, communications and language.

What biology shows us is that the uniqueness of being human lies exclusively in a social structural coupling that occurs through languaging, generating (a) the regularities proper to the human social dynamics, for example, individual identity and self-consciousness, and (b) the recursive social dynamics that entails a reflection enabling us to see that as human beings we have only the world which we create with others—whether we like them or not.

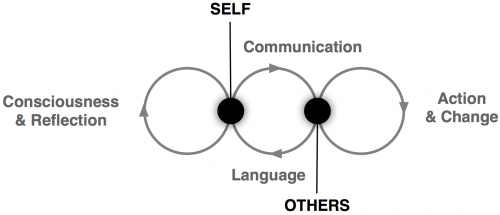

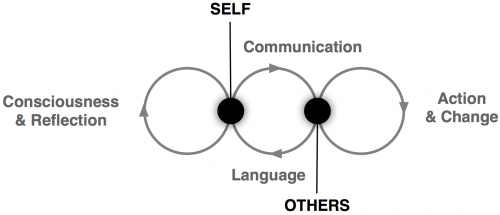

What I like most is the circular nature of the self-conception of individuals being tied to their use of language; the strength and ability of that language is tied to the richness and diversity of their interactions with others; those interactions are communication—strongly defined as activities triggering a change in the recipient; that change affects the individual’s own self-conception and consciousness. It’s a little heady, so I made up a graphic:

All of the components are core to our human reality. And, recursively, we cannot describe this reality without them.

On the practical side, I think the tidyness in which language and communication are linked and allowed to dynamically affect one another is astounding. Language—not just as words, but as a means of communicating and affecting change in others—is a continuous development. Our individual ability to language is a function of the richness of our interactions with others, continuously enriching itself as we add new experience to it, and use it to create descriptions of descriptions (and so forth) of those experiences. And, that the effectiveness of our language is the measure of our ability to communicate—effecting change—with others.

This calls to mind (well, it does for me) the thoughts of the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin who advanced the idea of the dialogic within literature, stating things along the lines that “a dialogic work carries on a continual dialogue with other works of literature and other authors. It does not merely answer, correct, silence, or extend a previous work, but informs and is continually informed by the previous work.” Expanding this:

For Bakhtin, all language - indeed, all thought - appeared dialogic. This means that everything anybody ever says always exists in response to things that have been said before and in anticipation of things that will be said in response. We never, in other words, speak in a vacuum. As a result, all language (and the ideas which language contains and communicates) is dynamic, relational and engaged in a process of endless redescriptions of the world. [from Wikipedia, though you can read much more advanced dissertation on Bakhtin]

The unbroken linearity of consciousness is interesting enough. Once we have experienced something, we cannot go back and un-experience it. I have participated in many conversations of “What album do you wish you could listen to for the first time again?” (for me it’s The Clash, The Clash). Jorge Luis Borges explores it within the short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”:

Those who have insinuated that Menard devoted his life to writing a contemporary Quixote besmirch his illustirous memory. Pierre Menard did not want to compose annother Quixote, which surely is easy enough—he wanted to compose the Quixote. Nor, surely, need one be obliged to note that his goal was never a mechanical transcription of the original; he had no intention of copying it. His admirable ambition was to produce a number of pages which coincided—word for word and line for line—with those of Miguel de Cervantes.