When the Puritans first landed in Massachusetts, they discovered a thing so curious about the Indians’ feelings for property that they felt called upon to give it a name. In 1764, when Thomas Hutchinson wrote his history of the colony, the term was already an old saying: “An Indian gift,” he told his readers, “is a proverbial expression signifying a present for which an equivalent return is expected.” We still use this, of course, and in an even broader sense, calling that friend an Indian giver who is so uncivilized as to ask us to return a gift he has given.

Imagine a scene. An Englishman comes into an Indian lodge, and his hosts, wishing to make their guest feel welcome, ask him to share a pipe of tobacco. Carved from a soft red stone, the pipe itself is a peace offering that has traditionally circulated among the local tribes, staying in each lodge for a time but always given away again sooner or later. And so the Indians, as is only polite among their people, give the pipe to their guest when he leaves. The Englishman is tickled pink. What a nice thing to send back to the British Museum! He takes it home and sets it on the mantelpiece. A time passes and the leaders of a neighboring tribe come to visit the colonist’s home. To his surprise he finds his guests have some expectation in regard to his pipe, and his translator finally explains to him that if he wishes to show his goodwill he should offer them a smoke and give them the pipe. In consternation the Englishman invents a phrase to describe these people with such a limited sense of private property. The opposite of “Indian giver” would be some thing like “white man keeper” (or maybe “capitalist”), that is, a person whose instinct is to remove property from circulation, to put it in a warehouse or museum (or, more to the point for capitalism, to lay it aside to be used for production).

The Indian giver (or the original one, at any rate) understood a cardinal property of the gift: whatever we have been given is supposed to be given away again, not kept. Or, if it is kept, something of similar value should move on in its stead, the way a billiard ball may stop when it sends another scurrying across the felt, its momentum transferred. You may keep your Christmas present, but it ceases to be a gift in the true sense unless you have given something else away. As it is passed along, the gift may be given back to the original donor, but this is not essential. In fact, it is better if the gift is not returned but is given instead to some new, third party. The only essential is this: the gift must always move. There are other forms of property that stand still, that mark a boundary or resist momentum, but the gift keeps going.

Tribal peoples usually distinguish between gifts and capital. Commonly they have a law that repeats the sensibility implicit in the idea of an Indian gift. “One man’s gift,” they say, “must not be another man’s capital.” Wendy James, a British social anthropogist, tells us that among the Uduk in northeast Africa, “any wealth transferred from one subclan to another, whether animals, grain or money, is in given away again, not kept. the nature of a gift, and should be consumed, and not invested for growth. If such transferred wealth is added to the subclan’s capital [cattle in this case] and kept for growth and investment, the subclan is regarded as being in an immoral relation of debt to the donors of the original gift.” If a pair of goats received as a gift from another subclan is kept to breed or to buy cattle, “there will be general complaint that the so-and-so’s are getting rich at someone else’s expense, behaving immorally by hoarding and investing gifts, and therefore being in a state of severe debt. It will be expected that they will soon suffer storm damage….”

The goats in this example move from one clan to another just as the stone pipemoved from person to person in my imaginary scene. And what happens then? If the object is a gift, it keeps moving, which in this case means that the man who received the goats throws a big party and everyone gets fed. The goats needn’t be given back, but they surely can’t be set aside to produce milk or more goats. And a new note has been added: the feeling that if a gift is not treated as such, if one form of property is convened into another, something horrible will happen. In folk tales the person who tries to hold on to a gift usually dies; in this anecdote the risk is “storm damage.” (What happens in fact to most tribal groups is worse than storm damage. Where someone manages to commercialize a tribe’s gift relationships the social fabric of the group is invariably destroyed.)

…Many of the most famous of the gift systems we know about center on food and treat durable goods as if they were food. The potlatch of the American Indians along the North Pacific coast was originally a “big feed.” At its simplest a potlatch was a feast lasting several days given by a member of a tribe who wanted his rank in the group to be publicly recognized. Marcel Mauss translates the verb “potlatch” as “to nourish” or “to consume.” Used as a noun, a “potlatch” is a “feeder” or “place to be satiated.” Potlatches included durable goods, but the point of the festival was to have these perish as if they were food. Houses were burned; ceremonial objects were broken and thrown into the sea. One of the potlatch tribes, the Haida, called their feasting “killing wealth.”

To say that the gift is used up, consumed and eaten sometimes means that it is truly destroyed as in these last examples, but more simply and accurately it means that the gift perishes for the person who gives it away. In gift exchange the transaction itself consumes the object. Now, it is true that something often comes back when a gift is given, but if this were made an explicit condition of the exchange, it wouldn’t be a gift….This, then, is how I use “consume” to speak of a gift—a gift is consumed when it moves from one hand to another with no assurance of anything in return. There is little difference, therefore, between its consumption and its movement. A market exchange has an equilibrium or stasis: you pay to balance the scale. But when you give a gift there is momentum, and the weight shifts from body to body.

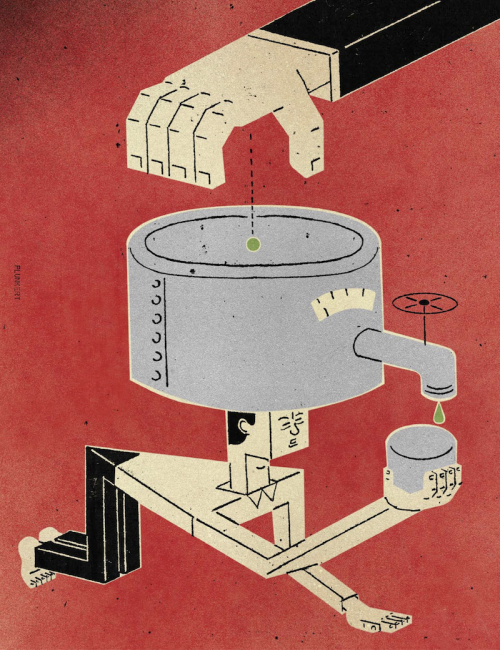

I must add one more word on what it is to consume, because the Western industrial world is famous for its “consumer goods” and they are not at all what I mean. Again, the difference is in the form of the exchange, a thing we can feel most concretely in the form of the goods themselves. I remember the time I went to my first rare book fair and saw how the first editions of Thoreau and Whitman and Crane had been carefully packaged in heat-shrunk plastic with the price tags on the inside. Somehow the simple addition of airtight plastic bags had transformed the books from vehicles of liveliness into commodities, like bread made with chemicals to keep it from perishing. In commodity exchange it’s as if the buyer and the seller were both in plastic bags; there’s none of the contact of a gift exchange. There is neither motion nor emotion because the whole point is to keep the balance, to make sure the exchange itself doesn’t consume anything or involve one person with another. Consumer goods are consumed by their owners, not by their exchange.

The desire to consume is a kind of lust. We long to have the world flow through us like air or food. We are thirsty and hungry for something that can only be carried inside bodies. But consumer goods merely bait this lust, they do not satisfy it. The consumer of commodities is invited to a meal without passion, a consumption that leads to neither satiation nor fire. He is a stranger seduced into feeding on the drippings of someone else’s capital without benefit of its inner nourishment, and he is hungry at the end of the meal, depressed and weary as we all feel when lust has dragged us from the house and led us to nothing.